Symbols in the brainSymbols are an integral part of the Bharatanatyam vocabulary, and we are taught specific mudras (a term used in yoga) or hand gestures (the term used in Bharatanatyam) that act as symbols to help us tell stories. For example, we use the “Mayura” hasta to show a peacock, and by extension, Lord Kartikeya who rides on a peacock. By showing a “Damaru” (a small, two-headed drum), we can show the actual musical instrument as well as Lord Shiva, who is often seen with a damaru. The Abhinaya Darpana (The Mirror of Gestures) contains and systematizes a large number of gestures and symbols for the Devas, the planets, famous emperors, seven oceans, famous rivers, trees, animals, flying creatures, and water creatures [1]. While many of these symbols are taught to us in a systematic way, the language of Bharatanatyam also gives the freedom for us to create new symbols. For example, below is a hasta I created after watching a mother bird feed her babies, and another hasta to show a (male) peacock with its wings and feathers at rest. I also conceived of a hasta to show a bat as it perches upside down a cave. As students of dance, we may not think of this in an obvious way, but by using symbols, we are engaging in semiotics or semiology, the study of “signs, symbols, and signification” [2]. Our brains and minds have a remarkable capacity to take these physical and visual descriptions and give them meaning. What is happening in the brain that helps us make sense of symbols and ascribe meaning to them? How is meaning represented in the brain?

The implications of this work are beyond the merely esoteric. For example, a study that did MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) set out to look at how we learn how to read and how our brains comprehend language from arbitrary visual symbols (i.e., alphabets) on a page. This study found a specific role of the ventral occipitotemporal cortex (vOT). The study showed remarkable specificity even within the vOT and revealed that there was a gradient such that at first, the rear part of the vOT was engaged, and then as the brain was understanding the meaning of the words, more forward parts of the vOT were involved [3]. One can hypothesize that the way symbols are transformed in Bharatanatyam may overlap in some ways with how we learn to read. There is much more to discover about how we perceive and give meaning to symbols. Bharatanatyam may be a tool to study this aspect of the brain’s functioning. In future posts, I will go through some of what we know from neuroscience on how we make sense of symbols! Citations:

0 Comments

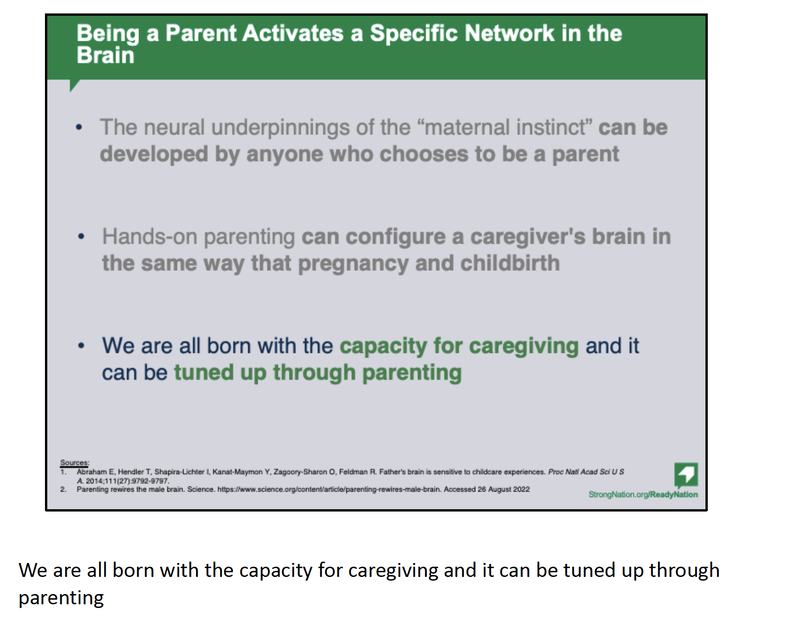

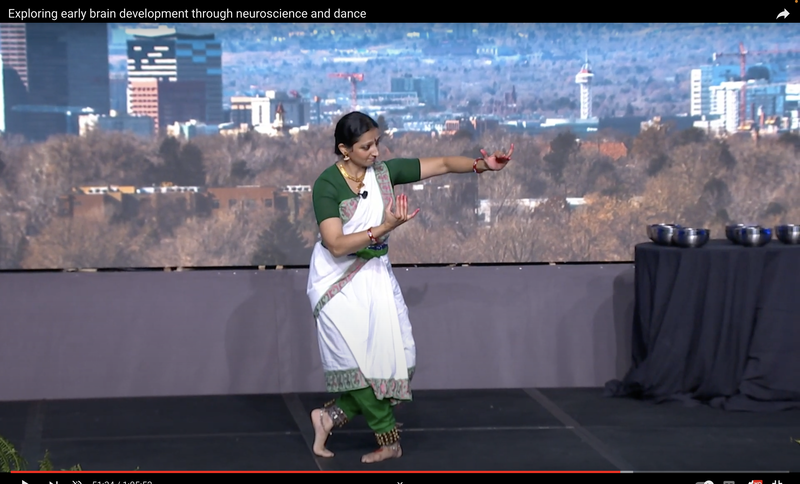

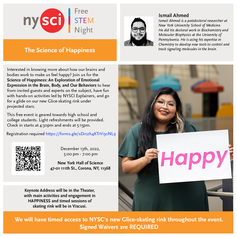

Invited to the NY Hall of Science to talk about happiness through dance and science In December 2022, I was invited by the New York Hall of Science to talk about the Science of happiness. The event is for teens where they will explore the "happiness experiment" at the museum and have the opportunity to "skate into happiness" on our new synthetic indoor ice rink. Participants will explore movement sequences, and I will talk talk about the intersection of neuroscience, dance and emotions, encouraging them to also share and even learn from each other. Caregiving practices change the brains of parents and other caregivers as well as the children they are supporting and play a key role in children’s future success. Scientists have discovered more about the impact that caregiving has on the brain—not only the child’s brain, but also the caregiver’s. Earlier in fall of 2022, I was honored to share some of what I’ve learned at the Parents as Teachers annual conference in Denver.

An article about this presentation can be found on this link. |

About SlokaMy name is Sloka. I am a neuroscientist and Bharatanatyam dancer; you can find more about me here. Archives

June 2024

|